If your brief reads “durable, repeatable, certifiable,” you’re not shopping for hobby prints—you’re choosing a production process. This guide compares polymer 3D printing technologies—SLS, FDM, SLA, and MJF—specifically for end‑use parts. We’ll center on mechanical performance and durability, then weigh throughput, repeatability, tolerances, finish, materials/regulatory readiness, cost/TCO, and post‑processing. You’ll get a quick verdict, a side‑by‑side table, and scenario picks for electronics housings, automotive brackets/ducts/fixtures, and consumer goods small‑batch runs.

TL;DR: If mechanical toughness and batch consistency are your North Star, powder‑bed nylon—SLS or MJF—usually wins for production housings, brackets, and fixtures because it balances strength, isotropy, and nesting efficiency. Choose SLA when cosmetic precision and tight tolerances dominate, and loads are modest. Choose industrial FDM when unit cost is paramount, and your loads, heat, and aesthetics requirements allow, or when you need high‑temperature polymers like PEI/ULTEM.

Quick side‑by‑side: Which process wins on durability and production realities

The table below maps the core trade‑offs for end‑use production. It reflects typical values and design guidance from authoritative sources. Always validate with your target material, geometry, and qualification plan.

| Criteria | SLS (powder‑bed laser) | MJF (powder‑bed inkjet+fuse) | FDM/FFF (filament extrusion) | SLA/VPP (photopolymer) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | A laser‑based powder‑bed fusion process that sinters nylon powder layer‑by‑layer to produce support‑free, durable polymer parts suited for batch production. | A powder‑bed process that deposits fusing agents with inkjet heads and fuses nylon powder, aimed at high throughput and consistent, isotropic nylon parts. | A filament‑extrusion process that deposits molten thermoplastic in beads; cost‑effective and able to use high‑temperature polymers but with layer‑directional anisotropy. | A vat photopolymerization process that cures liquid resin with light (SLA/DLP/VPP), delivering very high detail and smooth surfaces but resin‑dependent mechanical properties. |

| Mechanical durability | Nylon PA12 (TPM3D Precimid1172Pro): tensile ≈46 MPa; elongation at break ≈8–17%; flexural strength ≈51 MPa — see Precimid1172Pro PA12 material data (TPM3D) | Nylon PA12/PA11 with strong, uniform properties; excellent for functional parts | Engineering thermoplastics (ABS/ASA/PC/PEI) with clear anisotropy; can meet high‑temp needs | Excellent detail; mechanicals depend on resin; UV aging/embrittlement are considerations |

| Isotropy | Near‑balanced for filled and unfilled nylons | Very consistent property distribution across axes | Directional (Z is weaker); orientation critical | Generally uniform geometry; long‑term durability resin‑dependent |

| Typical tolerances | L≤100mm,±0.2mm

L>100mm,±0.2%×Lmm (source: TPM3D) |

Service typical ±0.012″ + 0.1% | Industrial FDM ±0.089 mm or ±0.0015 mm/mm (greater) | Small features can hit ±0.02–0.06 mm ranges |

| Surface finish | Fine, matte grain; vapor smoothing/dyeing common | Fine, slightly textured; smoothing/dyeing widely used | Visible layer lines; machining/finishing may be needed | Smoothest surfaces; paint‑ready with minimal work |

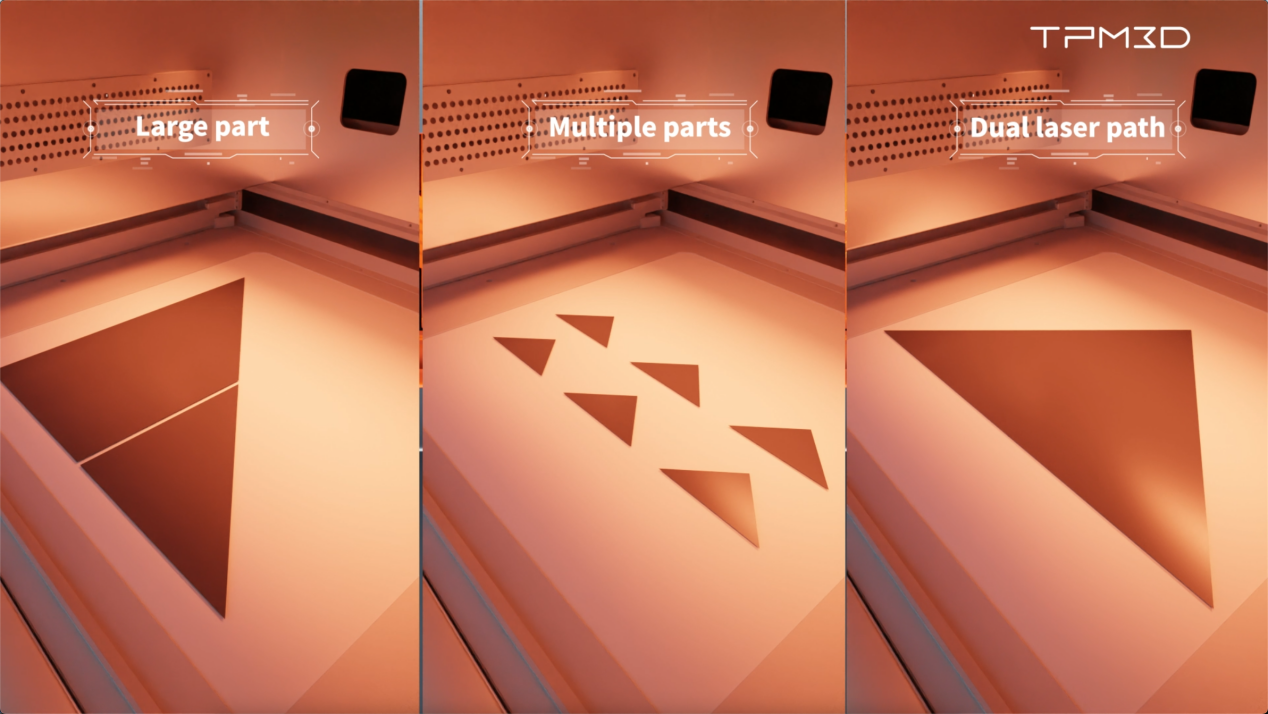

| Throughput & nesting | High packing density; large builds enable batch runs | High throughput workflows with swappable build units | Variable; many heads/fixtures drive labor | Good for cosmetic batches; support removal needed |

| Build chamber / max part size | Vendor dependent; common industrial SLS examples range from ~340×340×600 mm (e.g., EOS P3 NEXT) up to large‑format systems like TPM3D S600DL (600×600×800 mm). | Typical MJF build units commonly used in HP Jet Fusion 5000/5200 family are around 380×284×380 mm effective build volume with expandable build‑unit workflows. | Wide range; industrial FDM chambers vary by platform (from ~350×300×300 mm to larger gantry systems); suitability depends on chosen machine and part orientation. | Small‑to‑medium build volumes on production SLA platforms (typical XY footprints ~145×145 mm to ~300×300 mm; large‑format SLA exists but is less common); choose resin printer that matches part envelope. |

| Materials & certifications | Broad nylon family; biocompatible/FR grades available | Nylon portfolio with documented chemical resistance | PEI/ULTEM, PC, ABS, ASA; aerospace/transport usage | Biocompatible resins exist (case‑by‑case) |

| Cost‑per‑part (indicative) | Moderate; efficient nesting improves COGS at scale | Moderate; strong at volume due to cycle efficiency | Often lowest material cost; labor can dominate | Tooling‑quality looks; resin pricing varies |

| Design rules (supports) | Support‑free (powder supports); complex internals | Support‑free (powder supports); similar to SLS | Requires supports for overhangs; drain/clearance needed | Requires supports; careful orientation and cleanup |

| Best‑for scenarios | Durable housings, brackets, fixtures | Durable nylon parts at scale | Cost‑sensitive fixtures, large parts, high‑temp needs | Cosmetic panels, light pipes, precise small parts |

Reference anchors: nylon mechanicals and grades from TPM3D polymer pages; MJF PA12 data from HP materials documentation; FDM accuracy from a Stratasys F900 spec; SLA tolerances from Formlabs Form 4 design guide; service tolerance typicals from Protolabs.

- TPM3D lists representative PA12/PA11 properties on its polymer materials pages; see the nylon entries in the multipurpose/biocompatible sections in TPM3D polymer materials (2026) and related pages.

- HP publishes ASTM‑based mechanicals and handling guidance for PA12/PA11 in HP’s PA12 materials datasheet.

- Stratasys documents industrial FDM accuracy as ±0.089 mm or ±0.0015 mm/mm in the F900 product specification.

- Formlabs outlines SLA tolerance guidance (down to ±0.02–0.06 mm for small features) in the Form 4 design guide.

- Protolabs summarizes typical SLS/MJF service tolerances in 3D printing tolerances.

Independent cross‑process comparisons worth bookmarking:

- Comparative mechanicals for nylon PA12 across SLS and MJF using standardized tensile specimens and multiple build orientations are detailed in PMC’s 2024 open‑access study by Zakręcki et al., which reports ISO 527‑style tensile results (UTS, modulus, elongation) alongside flexural and impact tests.

- For dimensional accuracy benchmarking across AM processes on identical artifacts, see the ISO/ASTM 52902:2019 test artifact standard, a neutral framework widely used to assess geometric capability and tolerances across FDM/FFF, SLA/VPP, SLS, and MJF.

How to choose for electronics housings and functional prototypes

If your bill of requirements includes snap‑fits, thin walls, living hinges, and threaded bosses, nylon powder‑bed fusion—SLS or MJF—often gives the best mix of toughness, dimensional stability, and support‑free design. PA12 and PA11 deliver reliable elongation and fatigue behavior for latches and clips, and you can nest dozens to hundreds of housings per build to keep cycle economics in check. With post‑processing like bead‑blast, dyeing, or vapor smoothing, the parts look professional and withstand everyday use.

When to pick SLA: choose it for front bezels, cosmetic panels, light pipes, or small precise parts when the mechanical loads are low to moderate, and you need tight fits and paint‑ready surfaces out of the box. Just plan for support removal and consider resin aging if the part will see UV or heat.

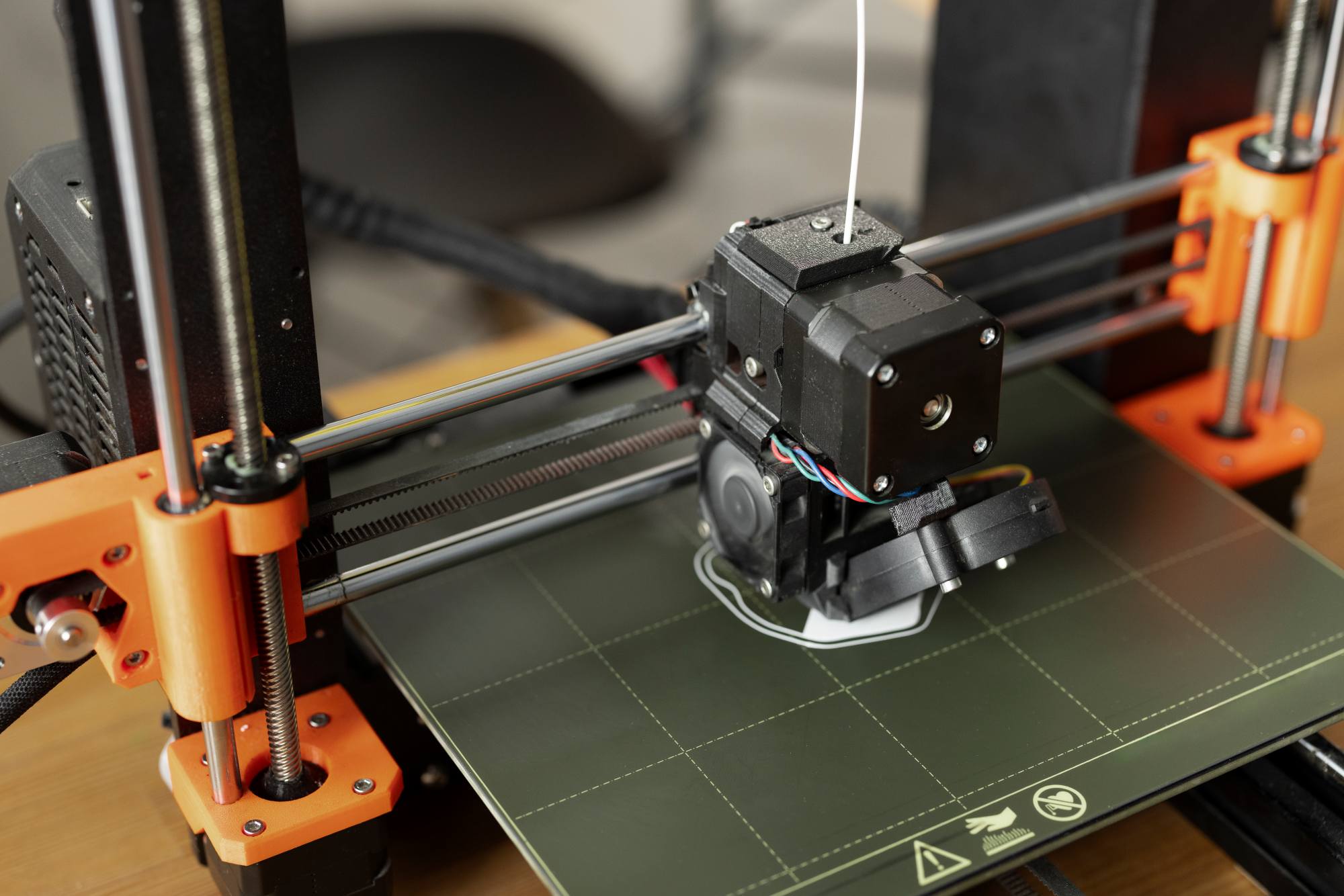

When FDM fits: larger housings and fixtures where visible layers are acceptable (or can be machined), particularly when cost or material type (e.g., PC, PEI) drives the choice. You’ll need careful orientation for snap‑fits and threads to avoid Z‑axis weakness.

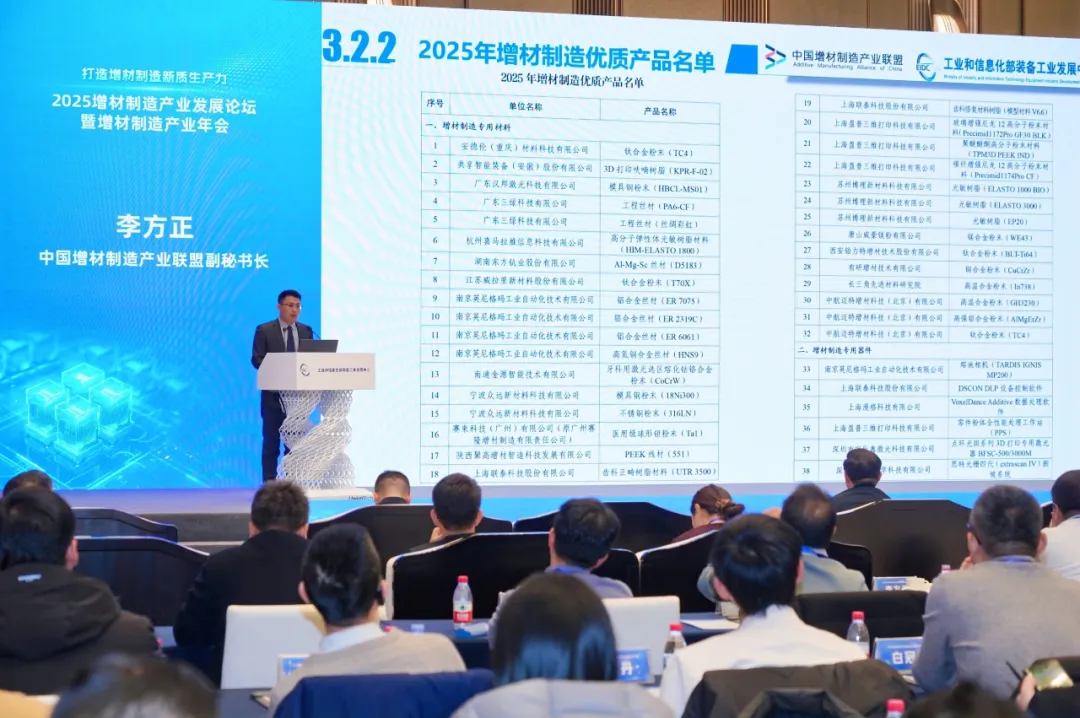

In a customer pilot for an electric‑tool housing, a supplier produced a 120×80×40 mm drill front housing in Precimid1172Pro GF30 BLK (glass‑filled PA12) with a 500‑part batch. Reported dimensional tolerance was ±0.15 mm on key bosses; failure‑mode testing cut the crack‑rate by 78% versus the prior CNC prototype. Parts passed environmental checks (AC 3750 V insulation test, leakage ≤20 mA; heat soak 135°C ±3°C). See the TPM3D customer case for electric housings for verification: TPM3D case — machinery & electronics applications.

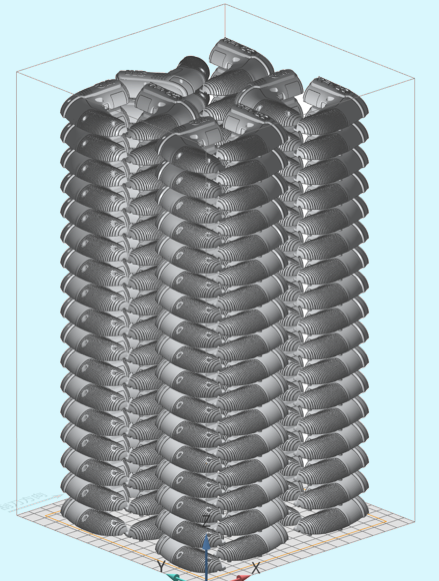

A quick capacity sketch: take a 120 × 80 × 40 mm housing. In SLS/MJF, you can often nest 60–120 units in a mid‑to‑large build volume, depending on wall thickness and packing strategy, translating to batch cycles measured in one to a few days, including cool‑down and finishing. Industrial FDM can parallelize across heads but typically requires more manual handling and support removal. For practical nesting guidance and large‑format considerations, see the SLS platform overview in TPM3D S‑Series industrial SLS printers.

How to choose for automotive brackets, ducts, and fixtures

Automotive duty cycles stress parts with heat, oils, and impact. Nylon PA12/PA11 from SLS or MJF is a strong baseline for brackets and ducts because it balances tensile strength, elongation, and chemical resistance to common automotive fluids. TPM3D, for example, documents PA12 performance and chemical classifications in its materials documentation; see TPM3D’s PA12 materials datasheet for example properties and handling guidance.

When elevated temperature is the dominant constraint (under‑hood environments, near heat sources), industrial FDM with PEI (ULTEM 9085) or PC can be the better choice, accepting anisotropy and finishing effort in exchange for temperature ratings and established transport/aerospace usage. SLA generally plays a cosmetic or low‑load role in the vehicle interior where precise fit and finish matter, but mechanical loads are limited.

A quick qualification sketch: for a duct bracket with multi‑axial loads, test SLS/MJF nylon coupons in X/Y/Z to verify property balance, then run orientation studies on the part to confirm safety margins. If the installation environment demands 120–150°C continuous service, compare FDM PEI/PC to see whether the thermal requirement outweighs the isotropy advantage of powder‑bed nylon.

How to choose for consumer goods enclosures and small‑batch runs

Consumer products live or die on look and feel—but they also have to survive drops, flexing, and daily abrasion. SLA will get you the most cosmetic surface and crispest details with relatively light finishing, which is appealing for housings, bezels, and visible components. For enclosures that get tossed into backpacks or mounted on bikes, SLS/MJF nylon better balances cosmetics (post‑finishable) with toughness and snap‑fit reliability. When cost pressure is intense and the use case is gentle, FDM can serve—just factor in support removal and any paint or smoothing steps to reach your target quality.

On finishing, plan a repeatable workflow. Powder‑bed nylon takes well to bead‑blast, dyeing, and chemical vapor smoothing to improve sealing and cleanability. For a deeper look at nylon SLS production considerations, see the expert overview in Mastering Polymer AM: TPM3D Industrial SLS Printers.

Decision cheatsheet: SLS vs FDM vs SLA vs MJF

Here’s the deal—pick by the hero criterion first, then by scale and finish:

- If durable, repeatable nylon parts with support‑free internal features are your priority for batches of 50–5,000+, choose SLS or MJF. Powder‑bed fusion gives you balanced mechanicals and dense nesting, which keeps unit costs predictable as you scale.

- If cosmetic precision and tight tolerances dominate and loads are low to moderate, choose SLA. It shines for front‑facing parts, detailed features, and paint‑ready surfaces.

- If the budget rules and loads are modest—or you need high‑temperature polymers—choose industrial FDM. Use orientation and infill strategies to mitigate anisotropy, and plan for finishing when aesthetics matter.

Pricing, TCO, and qualification caveats (as of 2026‑01‑23)

Cost per part is a function of machine hour cost, material cost and yield, labor (unpacking, support/powder removal, finishing), energy/maintenance, scrap/reprint rates, and overhead. A simple model many teams use is:

Cost per part ≈ (Machine hourly × Print hours ÷ Parts per build) + (Material cost × Net kg per part ÷ Reuse yield) + (Labor rate × Minutes per part ÷ 60) + (Allocated overhead)

Two reminders: effective packing density (for SLS/MJF) and support/finish time (for FDM/SLA) often swing the economics more than raw material prices. For a structured comparison of powder‑bed fusion vs. extrusion economics, see RapidMade’s primer in Powder Bed Fusion (MJF/SLS) vs FDM for Industrial Tooling. Pricing, refresh ratios, and labor rates vary by region and supplier, and they change—always request current quotes and validate your yields on representative parts.

Qualification steps (short list): lock material and supplier, run orientation coupons, define a process control plan (build layout, refresh rates, inspection protocol), document finishing, and complete environmental/aging tests where applicable. Want to test SLS without capex? You can pilot runs through a production service; for example, TPM3D lists a neutral entry point at 3D Printing Services.

Also consider

Disclosure: TPM3D is our product. If you’re leaning toward SLS for durable nylon parts at batch scale, TPM3D’s platforms are particularly strong for large, efficiently nested builds and established depowdering/smoothing workflows; see the neutral overview at TPM3D S‑Series industrial SLS printers.

FAQ

- Which technology is best for durable end‑use polymer parts? For nylon parts that must survive daily use with balanced strength and elongation, SLS and MJF typically lead because powder‑bed fusion approaches isotropy and supports complex, support‑free designs. Datasheets from TPM3D and HP back nylon mechanicals used in production housings and brackets; see TPM3D polymer materials and HP’s PA12 materials datasheet.

- Is MJF stronger than SLS? It depends on the exact material, machine, and parameters. Many MJF studies show tight property distribution across orientations, while SLS with unfilled nylons is also robust; test coupons in your target orientation and compare variance and refresh rates in your control plan.

- When should I choose SLA over SLS for production parts? Choose SLA when surface quality and precision are paramount and mechanical loads are low to moderate—think cosmetic panels, light pipes, small precise components. Tolerance guidance is documented in the Formlabs Form 4 design guide.

- How do I estimate cost per part for SLS vs FDM? Start with the simple formula above, then adjust for packing density (SLS/MJF) and support removal/finishing time (FDM/SLA). Bench a representative part at a qualified service to validate machine hour assumptions and yields.

- Can polymer 3D‑printed parts be certified for medical or regulated use? Yes, with the right materials and a qualification dossier. For example, nylon powders can be biocompatible in specific grades, and SLA offers biocompatible resins for defined applications; approvals are material‑ and application‑specific and require documented testing.

Choosing between SLS, FDM, SLA, and MJF ultimately comes down to the loads your part must survive, the environment it lives in, and the scale you intend to run. Pick your hero requirement first—durability, finish, cost, or throughput—then back it up with a measured qualification plan. What’s the first part you’ll trial to build your data set?